Forecasters Say State Needs Above-normal Precipitation To Make Up For Dry Winter

Above-normal precipitation in February across most of the state provided a much-needed boost to Montana’s meager winter snowpack, but forecasters said this week that a few more solid snowstorms over the next two months and a wet spring are needed to avoid a summer of expanding drought and below-normal streamflows.

The Governor’s Drought and Water Supply Advisory Committee met Thursday to discuss current conditions surrounding drought, snowpack and water supply a day after the U.S. Department of Agriculture’s Natural Resources Conservation Service released its outlook for the month ahead.

“The last couple of years, or at least last year, we were saying normal conditions are going to get us there,” said Troy Blandford, the water information lead for the Montana State Library. “I think we really need to see above normal, and not just for the next month or two, we need to see it for the next three [months], probably even into June, to really be in good shape for July.”

At the start of the year, more than half of the NRCS snow-monitoring sites in Montana were showing either their lowest or second lowest snowpacks on record, and little changed across most of Montana through January. Most river basins in Montana were at 40 to 60 percent of their normal snowpack levels to start February.

But a steady stream of storms last month brought above-normal precipitation to every river basin in the state except for the northern Bighorn Mountains – ranging from 110 percent of normal in the Bitterroot to 170 percent in the Upper Missouri basin, according the NRCS Water Supply Specialist Eric Larson, who also presented at the meeting.

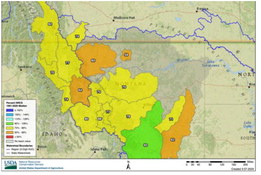

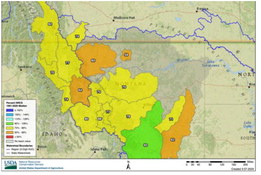

That helped most of the state’s river basins, though it did not fully make up for what had been one of the driest starts to winter on record in many areas of the state. As of Thursday, all of the state’s river basins sat between 59 and 86 percent of their normal snow-water equivalent compared to 1991-2020 levels except for the Bighorn basin, which was at 93 percent due mostly to snow from October’s heavy storm sticking around through the early winter months, Larson said.

But lower elevations are generally doing better snowpack wise than higher elevations, he said, noting some of the higher elevation SNOTEL sites are seeing snow-water equivalent deficits of up to 8 to 12 inches and would need several feet of snow to get to their normal levels. The statewide average snowpack as of Thursday was 11 inches of snow-water equivalent – roughly two inches above the record low since 1991 of 9.1 inches for March 7, a record established in 2001.

The median peak date for snowpack in Montana from 1991-2020 is April 14 at about 18 inches of snow-water equivalent, and Larson and other experts who spoke at Thursday’s meeting said the next six weeks could set the tone for how the rest of the year plays out in terms of water and drought. “So, think about today’s snow-water equivalent at all those SNOTEL sites. That’s how far we have to go to get to normal peak value,” Larson said.

Over the past decade, March and April brought above-average snowfall in 2014, 2017 and 2018. But the opposite was true in 2015, 2020 and 2021, and the NRCS said it hoped the February snow pattern would be a sign of what’s to come for the next two months, lest warmer and sunny weather zap the snowpack that does remain.

Snowpack is the biggest driver of Montana’s water supply, and Larson said current forecasts mirror that of the snowpack. Streamflows from April to July are currently expected to be about 60 to 80 percent of normal, but the Bighorn, Kootenai and Pend Oreille basins could have water years closer to normal because their snowpacks are closer to average levels.

But Larson and others also reiterated that May and June are typically the wettest months for nearly all of Montana’s counties, so even if the snow doesn’t fly this spring, soaking rains heading into the summer could help make up for the water deficits.

The precipitation is also key for soil moisture and drought, and the lack of it has led to a drought expansion since the start of the water year in October, which Department of Natural Resources and Conservation Drought Program Manager Michael Downey said was atypical in Montana. He said over the past 24 years, this winter is only the third time drought has increased in January and February, along with the 2000-01 winter and the 200910 winter. But drought conditions also improved into the summer in each of those years, he said.

About 95 percent of Montana is currently dry, but nearly half the state is seeing moderate drought or worse, and nearly one-quarter of the state is experiencing severe drought, according to this week’s U.S. Drought Monitor report released Thursday. Downey outlined the potential responses the state could make in the event widespread drought persists into the growing season under the new state drought plan and said he would be watching closely and working with other state and federal officials to determine the correct messaging and response if that is the case. “That is the time when we are most concerned about drought, because as Troy pointed out, we are now kind of just moving into our largest precipitation months across most of Montana,” he said. “We’re kind of at the wait-and-see stage.”

The National Weather Service’s Climate Prediction Center is forecasting above-average temperatures and just slight-below average precipitation for the next 1-2 weeks, and average temperatures and precipitation over the next month.

But the seasonal outlook for drought through May shows persistent drought on the western side of the Continental Divide in Montana, along the border with Wyoming, and in far northeastern Montana, and likely developing drought throughout central Montana.

DNRC director Amanda Kaster said 11 of the 15 state water project reservoirs were above 100 percent normal levels for this time of year, a good thing, she said, while the Department of Environmental Quality said it was closely watching forecasts and gearing up for possible widespread algae blooms if water temperatures get warm enough this summer.

Montana isn’t alone in dealing with El Niño’s dry and warm pattern this winter. More than half of the monitoring stations in the Western U.S. are below the 30th percentile for snow-water equivalent for the winter, focused particularly in Washington, western Montana, northern Idaho and northern Wyoming, according to the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration.

Blandford said the changes this spring and heading into the fall, if they come true, could be beneficial.

“I think the latest is that we’re going to move more into neutral come April. That could be favorable for us; it could mean that we get back into the normal spring weather patterns that we’re used to seeing,” he said. “And then, by late fall, we might slip into a La Niña that can be favorable for us for next winter.”