Forecasts Show Dry Summers Could Transition To Cold, Snowier Winter

Montana’s summer was among the top 30 warmest and driest the state has seen during the past 130 years, causing drought to reach extreme levels in southwestern and the easternmost stretches of the state and leading to federal drought disaster designations for more than 20 counties.

Rain that fell across nearly all of Montana earlier last week, including a wide swath of central Montana that received more than 2 inches, was a reprieve for areas of the state that have been largely dry throughout the summer.

And while short-term forecasts for the next two weeks show a likely return to above-average temperatures and drier conditions, longer term forecasts show a possible moderate La Niña developing that historically brings well-below-average temperatures and often above-average precipitation to Montana in the heart of the winter. Current models hint at a turnaround from last winter, which was one of the driest in terms of snow in Montana in three decades.

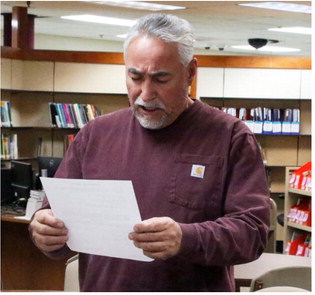

June through August marked the 19th warmest and 27th driest periods for those months in Montana dating back to 1895, Illinois State Climatologist Trent Ford said Thursday in the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration’s monthly climate and drought outlook presentation for the north-central U.S., which includes Montana. For the entire United States, the summer was the fourth warmest on record, Ford said. Aug. 31 marked the end of meteorological summer.

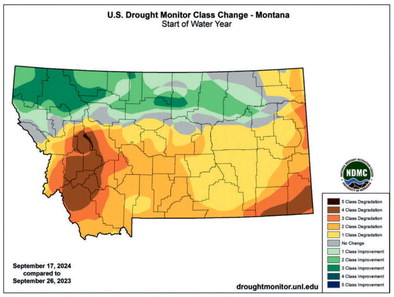

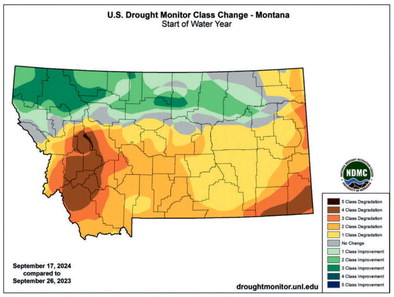

Oct. 1 will mark the start of the new water year, and compared to the start of the current water year, Montana will likely start the period with about twice as much land that is either moderately dry or experiencing drought as it did on Oct. 1 last year.

Thursday’s weekly U.S. Drought Monitor report, released each Thursday, found 100 percent of the state is moderately dry and 59 percent of Montana is seeing moderate or worse drought. About 9 percent of the state is experiencing extreme drought, primarily in southwestern Montana but also in the far northeastern and southeastern corners of the state.

That is largely unchanged from the beginning of summer in mid-June, though drought levels have changed from moderate to severe or worse drought across about 25 percent of Montana during that time.

Through mid-August, the U.S. Department of Agriculture had designated 21 Montana counties as primary natural disaster areas due to drought, making them eligible for Farm Service Agency loans.

The extreme drought in southeastern Montana is partially to blame for the spread of the Remington and House Draw Fires, the U.S. Drought Monitor said Thursday, which burned more than 370,000 acres of mostly rangeland in Montana and Wyoming. Gov. Greg Gianforte requested a USDA disaster declaration for the Remington Fire on Wednesday.

On Sept. 26 last year, 56 percent of Montana was drought-free, primarily south of the Hi-Line, while the northwestern stretches of Montana from Lincoln County east to Liberty County were experiencing exceptional drought.

Across the north-central U.S. region, it has been the driest Aug. 1 through Sept. 15 since 1976 and the fifth driest since 1951, Ford said, despite a blast of cooler air in late August. Some areas of the plains and eastern Midwest have gone more than a month without rain, and Ford called drought the “biggest story” of the region currently.

As of Thursday, about three-quarters of Montana’s subsoils are short to very short of moisture, Ford explained, and 57 percent of Montana was reporting poor to very poor pasture conditions, up 10 percent from last week. That is despite nearly all of Montana receiving rain this week. Northwest Montana largely saw less than a quarter-inch of rain. But southeast Montana and most of southwest Montana saw at least that much, including nearly an inch on the south side of Flathead Lake and more than an inch in a line stretching from Glendive up to Wolf Point.

Bozeman, Livingston and Billings all received more than an inch of rain this week, while stations across central Montana reported more than two inches — and some well above that.

The Lewistown Airport station reported 5.15 inches of rain this week through Thursday, and a station in Chinook also recorded 5 inches of rain.

Helena, Great Falls, Havre, Lewistown, Bozeman, Billings and Missoula have now all started September with above-average precipitation for the month, and all are now within an inch and a half, or even above, their average precipitation for the year through mid-September, according to National Weather Service records.

The U.S. Drought Monitor compiles its weekly reports on Tuesdays, so next week’s report could show how this week’s rain affected drought across Montana.

While current forecasts show this week’s rain might have been something Montanans will have to remember fondly for the next couple of weeks, as 6-10 and 8-14 day outlooks from NOAA show above-average temperatures and below-average precipitation, the one-month outlook for Montana shows equal chances of near normal precipitation and temperatures, and longer term forecasts are showing what would be typical for a La Niña winter.

The current El Niño/ Southern Oscillation forecast shows a 71 percent chance La Niña develops between September and November and persists through March. Ford said there is currently a 45 percent chance it would be a moderate La Niña event.

Ford showed data showing that since 1990, La Niña events typically bring warmer than average temperatures to Montana, particularly the eastern side, in October and November, along with average precipitation.

But during December, January and February, La Niña winters during the past 35 years have consistently brought well-below-average temperatures to all of Montana and above-average precipitation to western Montana.

Current forecasts from the Climate Prediction Center show below-normal temperatures creeping into Montana during the December- January-February period and staying in place through the March-April-May period for most of the state.

Similarly, forecasts show above-average precipitation chances starting in the October- November-December period and lasting through the February-March-April period, typically one of the wettest parts of Montana’s winters.

Natural Resources Conservation Service snowpack data show more than half of La Niña winters since 1990 have produced above-average snowpacks overall, but have also occasionally been some of the more lackluster winters, including the 2000--01 winter which saw the least snowfall through March of any winter during that period.

Last winter, an El Niño winter, also was one of the least snowy statewide through early April, but a snowy and cool April and early May helped to stave off a quick melt-off.

“We’re expecting above normal temperatures throughout the rest of the fall, potentially switching to a cooler pattern if La Niña does take hold, especially in the northwest part of the region,” Ford said.

The Climate Prediction Center’s forecasts hints that meteorologists believe it will take hold. Along with the longer-term temperature and precipitation forecasts, the seasonal drought outlook through the end of December predicts drought will improve or disappear throughout western Montana and only persist in northeastern and southeastern parts of the state.