Habitat Conservation In Montana Undergoing ‘Sea Change’

Two years ago when Montana Fish, Wildlife and Parks quietly unveiled a proposal to put Habitat Montana funds toward 30- and 40-year conservation leases, proponents described it as a “new conservation planning tool” while opponents warned of a “sea change” that could weaken one of the state’s most popular habitat protection programs.

Now, with Fish and Wildlife Commission approval secured for the first round of Habitat Conservation Leases and another set of agreements open for public comment, Montanans are learning how the program works: An interested landowner describes their property’s potential for prairie, sagebrush or wetland habitat, outlines the public access they’d allow and notes their preference for a 30- or 40year conservation lease. FWP then evaluates and ranks the applications it receives, uses a basic formula to establish a lease value and forwards the most promising applications to the Montana Fish and Wildlife Commission for approval.

Familiarity has helped some skeptics in the conservation community become program proponents, while others are wary that the program is funneling millions of public dollars toward temporary habitat protections without fully explaining the threats those properties face or the ecological benefits Montanans stand to gain.

Most of the criticism the Conservation Lease Program has faced focuses on its potential to weaken Habitat Montana, which has protected hundreds of thousands of acres of wildlife habitat from development with land purchases and conservation easements. Since Habitat Montana’s inception in 1987, FWP has purchased dozens of properties and entered nearly 350,000 acres of private land into conservation easements, voluntary agreements landowners can pursue to permanently protect their properties from subdivision.

FWP Wildlife Division administrator Ken McDonald told Montana Free Press that the department is committed to habitat conservation and sees the Conservation Lease Program as an opportunity to give landowners a broader array of options to protect prairie, sagebrush and wetland habitats from development without removing agriculture as a potential use.

“Working with landowners is ultimately what we’re seeking to achieve, and this lease program is just another tool to help with that,” he said. “We’re actually pretty excited about the suite of projects that are hopefully going to get approved.”

Since Habitat Montana’s inception in 1987, FWP has purchased dozens of properties and entered nearly 350,000 acres of private land into conservation easements.

The department’s ambitions for the program are big: Over the next five years, it aims to put 500,000 acres of prairie habitat under 30- or 40-year conservation leases. To do that, it estimates it will need $35-40 million dollars of public funding, most of which it plans to pull from Habitat Montana funds, which are primarily composed of money from nonresident hunting licenses, and money made available to Montana by the Pittman-Robertson Wildlife Restoration Act, which channels taxes collected on ammunition, gun and bow sales toward state-directed wildlife conservation projects.

Bill Long, a retired land trust executive who previously worked for FWP as a resource economist, worries the state is shifting its focus toward less protective conservation leases at a time when growing numbers of Montanans are concerned about the loss of open space and wildlife habitat.

“Development pressure couldn’t be stronger than it is now,” Long said. “We have a limited amount of dirt out there. … If you’ve got x amount of money out there, you do the permanent [easements].”

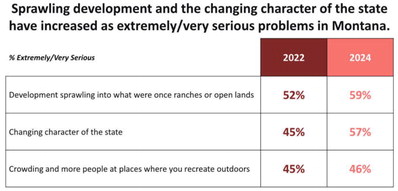

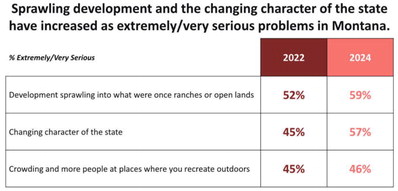

Recent polling bears out the development-related anxiety Long referenced. Earlier this year, 90% of registered Montana voters who participated in the University of Montana’s Crown of the Continent poll described development sprawling into open lands as a serious problem. Of those, 59% said it is a “very serious” issue, a seven percentage-point increase from 2022.

For Montana Wildlife Federation policy specialist Garrett Titus, the Habitat Conservation Lease Program includes some uncomfortable trade-offs.

In a recent interview, Titus said MWF prefers conservation easements over leases but “temporary leases are better than no leases” and putting money toward conservation leases is better than letting the Habitat Montana account sit idle. He added that while he appreciates the opportunity to secure access to some large and previously inaccessible tracts of land, MWF is also concerned that FWP may undermine landowners’ incentives to pursue permanent conservation easements by giving landowners the option of a termed lease.

To that end, he’d like the department to include more information about the development threats a property faces and a more rigorous accounting of a project’s economics — e.g., what FWP will spend on a given lease and greater detail about a parcel’s property value.

“If we could gain more transparency in the process, I think it would allow the public to sift through each of these leases individually,” he said.

Bradley Jones, a Helena attorney and sportsman who has been following the Habitat Lease Program’s development, echoed that assessment, expressing frustration that the department is poised to spend millions of dollars on projects described in fiveand six-page documents with virtually no information on the habitat and public access involved.

Jones said he wonders if projects are being equitably evaluated and if FWP is getting the “conservation bang for the buck” it should be getting with the program, which is supported by roughly $6 million of nonresident license sales that are deposited into the Habitat Montana fund annually.

“FWP has not disclosed the price being paid, has provided very little about the quality and scarcity of the habitat being saved for 30-40 years (i.e. the value to wildlife), provided scant information about the nature of recreation use that will be allowed, and generally is not demonstrating the cost-benefit analysis they should be,” he wrote in an email to MTFP. “With the cursory ‘notices,’ which look a lot like checklist environmental assessments, FWP has produced so far and the short comment period, FWP isn’t acting in the full spirit of information sharing and public participation contemplated by the Montana Environmental Policy Act.”

He pointed to one of the three proposals that’s out for a 30-day public comment period that ends Aug. 9. It involves the 52 Ranch’s pitch to put 18,255 acres of land spread between Dawson and Prairie counties into a 40-year conservation lease and allow 632 recreation days each year.

Beyond noting that the 52 Ranch has agreed to provide a contact name and phone number so the public can obtain access to the property and highlighting that at least 202 of those recreation days will be used for hunting from Sept. 1 to Jan. 1, there’s little information on the access component of the proposal. (52 Ranch did not respond to MTFP’s request for its comment, though FWP did share with MTFP that 52 Ranch will receive more than $2.1 million for the lease if it’s approved.)

A lack of information on public access is one of the primary concerns that John Sullivan, chair of the Montana Chapter of Backcountry Hunters and Anglers, has about the program.

“We’re using public dollars — Habitat Montana dollars — to pay private landowners to develop habitat, protect habitat. With that, there should be a very strong public access component [that’s] very heavily policed, regulated and outlined,” he said.

FWP’s McDonald countered that the department intends for the Conservation Lease Program Environmental Assessment that it adopted in 2022 to serve as a high-level vetting for projects so that each individual lease agreement doesn’t need lengthy environmental reviews and property appraisals, which can create a bottleneck at the agency. It could also, FWP maintains, give landowners a little more certainty regarding a proposal’s outcome.

One landowner who embarked on an ultimately fruitless five-year endeavor to put an FWP-administered conservation easement on his 23,000-acre family ranch northeast of Fort Benton knows all about lengthy waits and uncertain outcomes.

Steen Andreasen started talking with a local FWP biologist about putting a conservation easement on his 24,000-acre property in 2017 to meet a variety of goals: dig out from the generational debt he assumed to buy out members of his extended family, keep the fifth-generation farm and ranch in agricultural production and conserve the grassland that supports mule deer, antelope and a wide variety of waterfowl and upland birds such as sage grouse.

In addition to providing access to Andreasen’s ranch in Choteau County, the Chip Creek Conservation Easement would have opened public access to another 11,000 acres of land administered by the Bureau of Land Management and the Montana Department of Natural Resources and Conservation.

Andreasen told MTFP that he got along well with the FWP staffers he was in direct communication with but was informed in 2022 that the easement encountered opposition in Helena and was therefore stalled — indefinitely.

“Once it got into the political realm, then it got frustrating as all get-out,” he said.

Andreasen said that although he studiously avoids politics and the kind of elbow- rubbing that can grease the wheels of government bureaucracy, in 2021, he and his wife went to Helena to make their case to lawmakers for the easement, which, it should be noted, came with a $9 million price tag.

At the Capitol, he encountered a high-ranking FWP official who patted him on the back and assured him that he would do what he could to get Chip Creek across the finish line.

“He smoothed me over like politicians do, and off we went, thinking they’re going to be working on it. And then nothing happened,” he said. “I called, I left messages and never heard back. I figured how important I was to them guys.”

FWP Land and Water Program Manager Bill Schenk said there’s a bit more to the story than that. After Andreasen’s conversation with then-FWP Director Henry Worsech, Schenk continued advancing the proposal and eventually got it to a spot where FWP could carry it forward. By that time, however, Andreasen had already expressed interest in a conservation plan presented by a Wyoming-based carbon credit outfit called TerraWest, which had offered him money to help cover some of his bills. According to Schenk, that arrangement fell through.

Schenk acknowledges that FWP’s perpetual easements take time and wishes the agency could have reached an agreement with Andreasen, but a “timing mismatch” stymied their efforts.

Either way, Andreasen said he’s running up against a ticking clock and is entertaining any and all options. The ones that look the most likely aren’t that appealing to him, though — they involve selling to a Hutterrite colony, which would likely farm it intensively, or selling it to “an out-of-state somebody.”

“I’m plumb out of funds to keep operating and the bank has decided that they’ve heard enough so I can’t get operating funds,” he said.

While McDonald said he’s not familiar with that specific project, he did allude to some of the political dynamics that have made it more difficult for FWP to finalize conservation easements in recent years. The most notable change inserts the Land Board, which consists of the five top elected officials serving in state government, into the conservation easement process.

In response to a concern about the agency “orphaning” conservation easements, FWP highlighted some of the political hoops conservation agreements must pass through, including the Fish and Wildlife Commission’s approval and, for larger projects, the blessing of the Land Board.

The inclusion of the Land Board, which the Legislature authorized in 2021, is troublesome for public land access advocates because members of the board, such as Attorney General Austin Knudsen, have been vocal about their opposition to expanding FWP public land ownership, despite Montanans’ consistent support for public land access.

Though he can’t speak to securing an easement with FWP, Chase Hibbard of Cascade said he can provide some insight into the conversations his family had about partnering with the Montana Land Reliance to put a permanent conservation easement on their central Montana ranch.

He said there were plenty of fears associated with surrendering their right to subdivide the property, but his family has been “very, very happy with where we are and what we’ve done.”

Hibbard supports the conservation lease program and can appreciate why 30- or 40-year leases might feel less frightening to landowners than a perpetual easement, but he said his family has gained more with their arrangement than they’ve given up.

“We can sleep well at night knowing there’s never going to be condos on the hillside there,” he said. “Nothing that we were afraid of has materialized. It’s all been positive.”